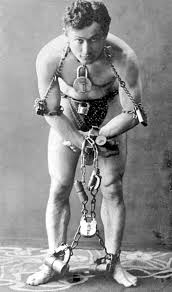

Harry Houdini died on Halloween. You know him as the greatest magician ever, but did you also know that he was an immigrant? Born Ehrich Weiss in 1874 in Budapest, Hungary (not Appleton, Wisconsin as he claimed), he and his family moved to the US when he was four and he later became a US citizen. Did you also know that he was an inventor? His acumen with technology was widely regarded during his lifetime. He borrowed some of his famous escape tricks from others, but, as it is the mother of invention, necessity required him to design the technology for his elaborate illusions. Companies today routinely bring in foreign technical experts and engineers to supplement their US workforce. Relying on immigrants can be tricky, however. Not only is there a bureaucratic morass with visas and naturalization, but US export laws may also be implicated. Apparently in disregard to the magician's credo, Houdini revealed technical secrets of some of his tricks. Sharing technology with a foreign national today may have hidden risks. Depending of the technology that is involved and the nationality of person to whom the technology is being shown, the Deemed Export Rule may require a company to first apply for and receive an export license from the US Government.

1 Comment

Halloween is as American as pumpkin pie. If you are anything like this writer, and given the explosion of all things Halloween, your house will soon be decorated with ghosts, witches, and monsters. You may even be seen wearing clothing with a Halloween theme. Some people are so overwhelmed by the spirit of the season that they put themselves at risk. Though an American tradition, most of our Halloween gear is manufactured overseas and then imported for domestic consumption. Classifying merchandise, almost by its definition, is a dry, painfully esoteric exercise, which explains why some people have a hard time passing the customs broker exam. But classification is the lynchpin of all import laws. Wars have been fought because of tariffs, or at least in large part because of tariffs. Tariffs emerge when diplomacy fails. Tariffs (how much in taxes you pay to the Government) are determined by the classification of your imported products. You classify products under the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States. In printed form, the HTSUS makes the Yellow Pages (remember those?) look like a comic book. Its heft is explained by the thousands of pages that list the tens of thousands of items. It is a "harmonized" schedule because our country coordinates with other countries on a model tariff schedule, thereby giving much predictability to both exports and imports regardless of which country you are doing business in. Predictability while classifying merchandise, that is. While tariffs have fallen a great deal worldwide in recent decades and tariff rates are increasingly determined by treaty, tariff rates can still vary wildly. Countries often use tariffs to protect domestic companies and even in this era of free trade are loath to open domestic markets to the vicissitudes of laissez faire. Rules of interpretation, both unique to the country to which the merchandise is being imported, and more general rules that cut across jurisdictions, parse the whole mess out. When you have tens of thousands of classifications and several ways, or rules of thumb, to determine the most accurate classification, there are bound to be disagreements. Which opens the system to an inevitable struggle between importers, who argue for classifications with the lower tariff rate, and Government, who argues the exact opposite because it feels its coffers threatened. That is why the court cases have the federal government on one side and the importer on the other side: US vs. Importer. The courts have decided several Halloween classification cases. What adds color and makes these cases almost tolerable and even fun to read is how the courts try to sound austere and formal while discussing the finer legal points of ghost bracelets, Frankenstein costumes, and jack-o-lanterns. Here are a couple of the more notable Halloween classification cases: Russ Berrie & Company vs. US - The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit is about as high as classification cases go (the next level up is the US Supreme Court). In this opinion, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the Court of International Trade and sided with US Customs and Border Protection. The controversy revolved around Halloween and Christmas earrings with the following motiffs: a Santa Claus; a snowman decorated with holly, wearing a top hat and holding a snowball; a teddy bear dressed in red and white Santa outfit and holding a present; red, green, gold bells with/or without red or green bows; a ghost; a jack-o-lantern; a Frankenstein monster; and a witch. The proper classification of these trinkets, according to the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, is "imitation jewelry" under heading 7117 of the HTSUS, not "[f]estive ··· articles" under heading 9505. Rubie's Costume Company v. US - While deciding the classification of Halloween merchandise, this case laid down an important rule with a much broader affect. The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit again slapped down the Court of International Trade and the Importer in favor of US Customs and Border Protection. The importer claimed that courts should give no deference to tariff classifications from CBP. Not so fast, said the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals. CBP may not be the final word on classification, but courts must pay attention and be guided to some degree by the agency's expertise -- sometimes. The level of deference courts give to CBP's classification decisions depends on how well CBP did its job, i.e., "The weight of such a judgment in a particular case will depend upon the thoroughness evident in its consideration, the validity of its reasoning, its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements, and all those factors which give power to persuade, if lacking power to control." In this case, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit found that it should defer substantially to CBP's classification ruling. Thus, court concluded that children's costumes of "Witch of the Webs", "Abdul Sheik of Arabia," "Pirate Boy," "Witch," and "Cute and Cuddly Clown" are properly classified as "festive articles" and not "wearing apparel," an obvious outcome if you are parent. Importers must report assists on their imported merchandise. It's not only that importers may have to eventually pay back duties owed to U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) on their undervalued merchandise, but the real hassle comes from the fines and penalties and the added scrutiny from CBP.

The alarming thing is that you can be tagged with liability even if you do not strictly enter the merchandise, but merely introduce. Let me explain. The US Court of the Appeals for the Federal Circuit just decided US vs. Trek Leather. The US Government had sued and won a judgment in the US Court of International Trade against the importer of men's suits for $45,245.39 in unpaid duties and $534,420.32 in penalties and interest. Most small importers would find it hard enough to come up with the $45K, but half a million dollars? Not even bankruptcy, which frowns upon debtors who owe customs duties and penalties, may be much of a haven. The importer provided fabric to the manufacturer of the suits free of charge or at a reduced costs. These were the assists. Importers often find it hard to grasp why assists are important or even what they are. The US Court of the Appeals for the Federal Circuit clarifies what was at stake: By providing the manufacturer free or subsidized components, like the "fabric assists" here, an importer reduces the manufacturer's costs, and the manufacturer may then reduce the price it charges for the merchandise once manufactured. A suit maker, if it obtains its fabric for free, might shave $100 off the price it charges for a suit. In this case, "[t]he material assists . . . were not part of the price actually paid or payable to the foreign manufacturers of the imported apparel." In such circumstances, the manufacturer's invoice price understates the actual value of the merchandise, and if the artificially low invoice price is used as the merchandise's value when calculating customs duties based on value, disregarding assists results in understating the duties owed. To address such an artificial reduction of customs duties, the statute and regulations expressly require that the value of an "assist" be incorporated in specified circumstances into the calculated value of imported merchandise used for determining the duties owed. In affirming the judgment against the importer, the US Court of the Appeals for the Federal Circuit reminded the trade community that liability for accurately reporting assists applies not just to the individuals and companies who enter the merchandise, but equally to those who introduce it. What's the difference? Here again is the court: Panama Hats confirms that, whatever the full scope of "enter" may be, "introduce" in section 1592(a)(1)(A) means that the statute is broad enough to reach acts beyond the act of filing with customs officials papers that "enter" goods into United States commerce. Panama Hats establishes that "introduce" is a flexible and broad term added to ensure that the statute was not restricted to the "technical" process of "entering" goods. It is broad enough to cover, among other things, actions completed before any formal entry filings made to effectuate release of imported goods. We need not attempt to define the reach of the term. Under the rationale of Panama Hats, the term covers actions that bring goods to the threshold of the process of entry by moving goods into CBP custody in the United States and providing critical documents (such as invoices indicating value) for use in the filing of papers for a contemplated release into United States commerce even if no release ever occurs. What Mr. Shadadpuri did comes within the common sense, flexible understanding of the "introduce" language of section 1592(a)(1)(A). He "imported men's suits through one or more of his companies." Gov't Facts at 1. While suits invoiced to one company were in transit, he "caused the shipments of the imported merchandise to be transferred" to Trek by "direct[ing]" the customs broker to make the transfer. Himself and through his aides, he sent manufacturers' invoices to the customs broker for the broker's use in completing the entry filings to secure release of the merchandise from CBP custody into United States commerce. By this activity, he did everything short of the final step of pre- paring the CBP Form 7501s and submitting them and other required papers to make formal entry. He thereby "introduced" the suits into United States commerce. Assists tend to be overlooked by importers, but the federal courts are clearly expanding liability for improper reporting of assists. It's time to sit up and pay attention. Need more information on CUSTOMS ASSISTS? Attend our webinar on Customs Assists, November 10, 2014.  US Customs and Border Protection just amended its policies regarding Focused Assessments, those intensive, prolonged, invasive audits of large importers. Employing the ascetic, some might suggest sadistic, philosophy of one who prefers to remove a bandaid slowly to maximize the duration of the discomfort, CBP decided that this is just the first big step of a greater overhaul that the agency plans to gradually roll out in the coming months and years. CBP claims without any sense of the irony that it is seeking to make focused assessments more nimble and malleable. If you are one of the lucky and increasingly rare large importers that hasn't been subjected to a focused assessments, CBP auditors have been clinical in their application of a series of highly technical standards that all importers are expected to comply with. If this sounds like the agony that schools inflict on our kids through standardized tests under Leave No Child Standing, you are getting the gist. CBP uses questionnaires, personnel interviews, document reviews, facility walk-through, and statistical sampling to gauge compliance and improvement and upon finding an indication that either is missing will elevate the risk level and therefore the audit to more punitive levels of intrusion and cost. If you are really naughty, the CBP auditors may even set up shop on a semi-permanent basis within your place of business. It's like having cops move in to your home just to make sure you tow the line. But CBP realizes that one size doesn't fit all and perhaps a more nuanced approach is needed. Here are the major changes (thus far): No More Advance Conferences: Before the audit even started, the importer and CBP audit team would meet in what could be seen as a test of wills. Armed with the answers to a lengthy questionnaire that the importer provided, CBP would interrogate the importer further to determine the scope the focused assessment, and the importer would gently but firmly deflect overreaching inquiries. Sadly, these preliminary scuffles are now gone (entrance conferences, however, will still be held) and CBP will rely more heavily on a review of the importer's policies and questionnaire answers. CBP has access to a wealth of the importer's data even before the importer is notified of the audit obviate the need for an interrogation. It is this data that allows the agency to decide which importers to audit. Much of the audit's scope, and certainly the contents of the questionnaire, are developed at this stage called the preliminary assessment of risk or PAR. Tailored Questionnaires: The importer will still be asked to complete an extensive questionnaire, but now it's called a Pre-Assessment Survey Questionnaire or PASQ. While CBP provides a template for PASQs, CBP auditors are expected to tailor the PASQ to fit the importer based largely on the impressions generated during the PAR. In addition, "Auditors use their judgment to develop the format and content of the questionnaire". Most of the changes to the Focused Assessment are about giving CBP auditors more discretion. The scope of the Focused Assessment, how the auditors pick samples of entry documents and what they look at during walk-through will rely more heavily on the auditors' judgment. The problem with greater discretion is that the risk of overreaching is also greater. CBP auditors are not bound by yesterday's methodologies and will be able to dig more deeply into areas of concern. Clearer Path to ISA: The Importer Self-Assessment (ISA) program is a gem that few importers take advantage of. A voluntary program from CBP, importers are allowed to audit and police themselves (CBP removes them from most audit pools) once they establish to CBP's satisfaction the soundness of their import policies. Because a Focused Assessment is more rigorous than ISA's qualifying procedures, companies that have successfully gone through a Focused Assessment are allowed a streamlined process to enroll in ISA. Want to know more about the Focused Assessment amendments and how to prepare and survive a Focused Assessment, then sign up for our webinar on Monday, October 13.  This 19th Century author wrote his famous novel about finding a certain letter in the attic of a customs house in Salem, Massachusetts. Who is he and what is the name of the novel? SPOILER ALERT: The correct answer is at the end of this article. The author wrote this novel, his first successful one, by building on his personal experiences in a customs house. His novel was America's first ever blockbuster novel with the public, generating desperately needed income for himself. He's related to one of the judges who tried the Salem witches two centuries earlier. Need more clues? Here's an excerpt from the famed Customs House introduction: But the object that most drew my attention, in the mysterious package, was a certain affair of fine red cloth, much worn and faded. There were traces about it of gold embroidery, which, however, was greatly frayed and defaced; so that none, or very little, of the glitter was left. It had been wrought, as was easy to perceive, with wonderful skill of needlework; and the stitch (as I am assured by ladies conversant with such mysteries) gives evidence of a now forgotten art, not to be recovered even by the process of picking out the threads. This rag of scarlet cloth,--for time, and wear, and a sacrilegious moth, had reduced it to little other than a rag,--on careful examination, assumed the shape of a letter. It was the capital letter A. By an accurate measurement, each limb proved to be precisely three inches and a quarter in length. It had been intended, there could be no doubt, as an ornamental article of dress; but how it was to be worn, or what rank, honor, and dignity, in by-past times, were signified by it, was a riddle which (so evanescent are the fashions of the world in these particulars) I saw little hope of solving. And yet it strangely interested me. My eyes fastened themselves upon the old scarlet letter, and would not be turned aside. Certainly, there was some deep meaning in it, most worthy of interpretation, and which, as it were, streamed forth from the mystic symbol, subtly communicating itself to my sensibilities, but evading the analysis of my mind. If you're still lost, Demi Moore starred in the much-panned 1995 movie version of the novel, a novel about a young woman who has an adulterous affair with Salem's minister. With the minister serving as inquisitor, the town tries the woman, finds here guilty, and forces her to wear a red letter "A". The woman accepts the town's and her secret lover's punishment, even as the minister descends into his private hell of shame. The Answer: Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter.  Intellectual property protection sees its most fiercest manifestation at our nation's borders. The border is where, for example, Samsung and Apple are duking it out over who gets to numb our brains and maim our social interactions with their gleaming rectangles of addicting apps and unwholesome tactile rituals they force upon us (I am an writing this on my iPad). The border is also where companies and individuals canregister their trademarks and copyrights with US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and, once done, CBP can forego any pretense of the usual due process surrounding IPR protection (IPR holders usually have to initiate court proceedings to protect their interests) and impound any merchandise indefinitely (or so it seems) upon the slightest suspicion of an infringement. At that point, good luck trying to convince CBP that it made a mistake or that the perceived infringement was trivial and inadvertent and, thus, deserving of dispensation. I am keen to protecting intellectual property, but it's been overdone to the detriment of both innovation and the common weal, the two reasons that those protections were ostensibly put in place. Case in point, US Customs and Border Protection just announced that it has trademarked its C-TPAT logo. This triggered a double-take from me. C-TPAT has never been known in its two-decades of plodding existence for regulatory refinement or initiative. Except for a few cosmetic changes, it's been the same catatonic C-TPAT from the beginning. It's gotten bigger, but not prettier. A couple of days ago, C-TPAT sent this announcement to program participants: The Customs-Trade Partnership Against Terrorism (C-TPAT) program has applied to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for a trademark on its logo to protect the program against the misuse of the logo and deceptive business practices. C-TPAT worked with the Office of Public Affairs within U.S. Customs and Border Protection and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of the General Counsel, the office responsible for overseeing the DHS Intellectual Property Policy, to complete this task. All licensing agreements will be issued free-of-charge. The C-TPAT Partner Agreement will be updated within the C-TPAT Portal to include clauses describing the proper use of the logo. When each Partner completes their annual profile review and re-signs the Agreement, they will also be agreeing to the proper use clauses. Until such time as a Partner's next annual review, Partners are authorized to continue current uses of the trademark. Partners who are removed or withdrawn from the C-TPAT program must cease using the trademark. Note the display of the trademark does not denote program status; only the Status Verification Interface within the C-TPAT Portal verifies current program status. At this time the C-TPAT trademark is being licensed only to C-TPAT Partners, as a benefit for continued program membership. In addition, a method already exists to record the user agreement and identify the number of licensees. The C-TPAT program is developing a method external to the Portal to allow non-C-TPAT Partners to request and register use of the logo. There are huge problems with this notice. CBP sent it only to those companies already in C-TPAT (there is no Federal Register notice, for example), which reflects one of the most aggravating and delusional mindsets ever from an entrenched bureaucracy. C-TPAT does not like talking to, communicating with, assisting, or associating with individuals or companies who are not already in the program, and barely to those who are. The C-TPAT phone operators, it would be a stretch to call them counselors, who answer the well-hidden official C-TPAT phone line deflect queries from the public with "we refer you to the C-TPAT guidelines on our website," a ludicrous suggestion that exposes a level of bureaucratic ineptitude, indolence, and superfluousness that would make Ron Swanson proud. Some of the C-TPAT guidelines are of dubious, well, guidance. C-TPAT imposes on importers that their "buildings must be constructed of materials that resist unlawful entry." One can only infer that CBP is thankfully trying to exclude from C-TPAT the thousands of manufacturers, importers, customs brokers, and others who occupy facilities made out of Legos. The few helpful C-TPAT guidelines that exist are buried deep in the C-TPAT portal, which you can't enter unless you are C-TPAT certified. I must admit, however, that CBP has taken some valiant steps to upgrade its website in the past few weeks with promising results. However, CBP hosts a huge C-TPAT conference about once a year, but you can attend only if you are C-TPAT certified. Thus, the only companies that benefit are companies that supposedly have already been proven compliant by CBP's thorough vetting. In other words, no one benefits, at least not much, especially not the non-member riffraff trying to crash the party. I hear, however, that the mixers are dynamite. C-TPAT holds the public at arms-length ostensibly because it views itself as a volunteer program, the "partnership" of C-TPAT, not as a true government program. Funny how C-TPAT officials still carry federal badges and guns. It's a convenient (for CBP) hybrid. C-TPAT is codified in statute but I have no idea why. It's a silly statute that serves no purpose other than to remind the CBP Commissioner to continue with CBP. A good calendaring app, maybe even a string tied around the Commissioner's finger, would have worked just as well. CBP hasn't issued any regulations on C-TPAT, presumably because it doesn't want to be held accountable. The appeals process for companies who have been rejected or expelled from C-TPAT are ludicrously vague and provide no court review. CBP alone decides whether it acts reasonably in all C-TPAT matters, and we all know No doubt that CBP is trying to make sure that people and companies do not use its C-TPAT logo for personal gain or without CBP's imprimatur. From CBP actions, you would think that the C-TPAT logo is universally recognized and coveted. Like Nike's swoosh. CBP may even consider registering its trademark with its own IPR department to stop the flood of C-TPAT knockoffs that is surely diluting the worth of its priceless logo and engendering a seedy black market of unwholesome counterfeits. Walter White could make billions. But here's the problem. CBP is supposed to recruit companies into the C-TPAT program. Greater enrollment is the best way to secure our borders and shipments into our country. This is not a controversial claim. CBP has said so publicly many times and, if I had to dig through the legislative history, I would bet that Congress echoed the sentiment. CBP claims success in getting most large importers and logistics providers into C-TPAT, but the numbers appear to have stagnated and there is no visible push to increase enrollment. There is no discernible push to educate or help companies not already in C-TPAT. CBP should consider holding conventions and seminars for companies who are interested in joining. Even if CBP is happy with its enrollment numbers, which I guess is ok until suddenly it isn't ok, there remains its parochial, bordering on xenophobic, thinking. It's not only that CBP stands on shaky legal grounds when it tries to register a trademark. Are taxpayers supposed to ask for permission to use a symbol that they paid for? Are the stars and stripes or the US Constitution trademarkable? With this precedent, you may be forced to take a laser to that Abe Lincoln tattoo on your forearm or pay royalties to celebrate the 4th of July, which, granted, may have the unintended benefit of curtailing binge consumption of hot dogs. It looks like CBP may be jumping the gun. It announced that it applied for a trademark, not that it was granted one, and the tentativeness of this status should probably have given it pause before it laid down all sorts of rules, which the notice does, regarding what is allowed and what is forbidden. All this reveals an unwelcoming philosophy by a government agency for the people who paid for the creation of the logo and who fund every C-TPAT activity and CBP employee. But fortunately, again, for members, the hors d'oeuvres are killers. The law profession (people, mostly lawyers and judges, tell me it's not a business) pretends that lawyers don't, or at least, should't give out business advice. Tut tut, we only do law. You know, we stay above the fray while invoking obscure legal precedent. But other than the pro bono I've done, I can't remember a single case where money was not the crux of the matter. I appreciate why lawyers try to segregate legal advice from business advice (for example, to safeguard the attorney-client privilege), but I initiated a few lawsuits for clients who claimed to be motivated solely by principle and who vowed to spend whatever was needed to attain justice. It's funny how the pursuit of justice wilts under the weight of a couple a months of heavy billing even when success appears certain.

What lawyers do impacts, and sometimes dictates, the bottom line. That is why companies are reluctant to comply with laws, and do so only upon threat of near certain discovery and sanction by enforcement authorities. Our nation's foreign trade laws are all about money. It does not take a PhD in history or economics to know that nations, and increasingly blocs of nations, seek to control the flow of international trade for their own benefit and someone else's detriment. That there are winners and losers should not surprise any proponents of a market system. Just as there are no free meals, there is no free trade. When people say "free trade", what they really mean is that they want to rearrange duty rates and investment laws to benefit their preferred industries. Neither goods nor people travel unimpeded over national borders (yes, I know, the EU is somewhat of an exception). There is certainly little freedom to be found at our nation's borders. In fact, as those who travel overseas can attest, under the U.S. Supreme Court schema our constitutional freedoms and rights lose potency as we approach the border, you know, where you need them the most. Governments prefer constraining the populace, not themselves. They want the license to punish citizens and to those transacting with citizens. The assertion of authority is jurisdictional, which means countries reserve the legal means to extend their reach as much as possible to be able to whack you for perceived violations of their Our country, the good old USA, has extended its jurisdictional reach far beyond what other countries could ever dream or have the capacity of doing, but evidently not far enough. Which is why our government officially discourages the use of Foreign Principal Party Controlled Export Transactions (FPPCETs, presumably pronounced feppesets, or maybe not). Never heard of an FPPCET? I can't blame you. That's the new name that export authorities want to give for a routed export transaction. I'm happy for the name change. Routed transaction was always a stupid term. What shipment isn't routed? No one says, "Don't worry. We managed to ship your merchandise without any routing." Maybe when someone finally invents a Star Trek teleporter they'll be able to actually avoid moving merchandise to get it somewhere else, but until then, routing seems to an inevitable component, if not the embodiment, of any shipment. But maybe you don't know what an export routed transaction is either. In an FPPCET or routed export transaction, a foreign purchaser uses its own freight forwarder to arrange shipment from the domestic seller. What deceivingly looks like a domestic sale turns out to be an export when the party controlling and paying for the shipment is in a foreign country and thus beyond the reach of our enforcement authorities, which explains the antipathy from said authorities. But this type of transaction is too popular to overturn by regulatory edict, so our export authorities devised byzantine means to stay in the game, but fortunately some clarity is on the way. Under proposed revisions of both the Export Administration Regulations and the Foreign Trade Regulations, FPPCETs will be allowed if the Foreign Principal Party in Interest or FPPI hires a forwarder in the USA and signs over a power of attorney to the forwarder to do the export licensing work and clearance that is needed. The FPPI must deliver the name of its forwarder and a copy of the power of attorney to the US Principal Party in Interest or USPPI. The USPPI assigns in writing primary responsibility for determining licensing requirements and obtaining license authority to the FPPI and the FPPI acknowledges in writing that it is assuming this responsibility. Absence these steps, the USPPI remains the exporter. Now that the parties are fully apprised as to who is on first base, the USPPI must provide sufficient information to the FPPI or its forwarder to determine export licensing, but does not make that call itself. The proposed revisions to the regulations should improve awareness and compliance, although foot dragging is to be expected. Some USPPIs may howl that these new requirements are onerous, but all they really do is make sure that the parties communicate to each other and create a written record of who is controlling the shipment and who is on the hook if anything goes wrong. Forwarders may not like that their liability is so plainly agreed to and recorded by the parties thinking, wrongly, that they are merely and solely logistics providers. The uncomfortable truth is that the forwarder becomes the exporter by virtue of its domestic presence and the power of attorney from the FPPI. That clarity of roles should stem silly demands from forwarders asking USPPIs for licensing determinations and should encourage USPPIs to more visibly paper their interactions with foreign customers if they want to avoid being the exporters and all the attendant liability of these transactions. Will the proposed revisions to the regulations impact the bottom line of all parties to these transactions? Will it discourage the use of this kind of transaction or perhaps even reduce the volume of exports from our country? Don't ask me. I'm just a lawyer. You can find the BIS's proposed revisions on its website, by its citation (79 Fed. Reg. 7105 (February 6, 2014) , or by requesting a copy from yours truly. Unlike some other federal agencies, CBP makes its rulings available to the public and in searchable format through its online service called CROSS or Customs Rulings Online Search System. That's the upside. The downside is that the majority of the rulings do not provide helpful analysis. Indeed, most provide scant illumination and this lack of logic undermines the value of this online cache, but weirdly allows a lawyer to perform wonders on your behalf.

Our nation's laws (state and federal) are premised on transparent, readily available precedent. We have so many rules, statutes, and regulations that the people interpreting these look to how other arbiters decided similar fact situations. Of course, similar does not mean duplicate, so rules of thumb are needed (called the General Rules of Interpretation in tariff classification parlance), as is the logic that was previously employed. It is decision-making by analogy. Previous rulings or opinions are consulted not just because they are helpful, but because earlier precedent must be followed to the extent it is applicable. A precedent is given greater influence if a superior authority within the same chain of command hands it down. It is a Byzantine construct that even lawyers and judges can find dizzying, but its organic, malleable nature allows for limited self-correcting to take place. This is where it pays to use a lawyer. Lawyers, if they are worthy of their licenses, appreciate that there are few absolutes, few areas where the law is permanently, indelibly carved in marble. A competent legal advocate comes in handy when importers request CBP rulings, sometimes even overturning what appeared to be iron-clad precedent. CBP concedes that it makes mistakes by periodically issuing Revocations Letters published in the Customs Bulletin and on CROSS. CBP appreciates that its own rulings shouldn't even be followed. This is not surprising. CBP officials who issue rulings rarely undergo legal training. They may unthinkingly follow shoddy rulings issued by CBP and ignore court cases that go the other way. The point is don't automatically give up even in the face of CBP rulings that seem to go against your interests. It's possible that CBP's rulings that bar your way are wrong and are mere eggshells awaiting to be pulverized at the feet of your irresistible logic. View all your submissions, not just ruling requests, to the government as opportunities to advocate. You should not expect great results if you are submitting bare bones, cookie cutter requests for binding rulings. Make your arguments compelling from the get-go. Invoke overwhelming legal precedent to support your stance. There is much at stake. Not only should you be trying to avoid classification penalties (CBP reserves the right to issue these whenever an importer misclassifies imported items even when there is no duty loss), but you also trying to limit any import duties that you have to pay. Texas Lawyer

June 11, 2012 Businesses employ all manner of legal strategies to protect their intellectual property rights, but some legal departments overlook the potent enforcement tools available at the border. The United States imports an enormous amount of goods from other countries, and pirated products naturally are part of that deluge. In-house counsel should understand how to enlist the federal government's help to stop infringing goods or, alternatively, to defend their companies' rights to import products against claims of infringement. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) is the gatekeeper for products entering the United States, with enormous powers and vast resources at its disposal to keep out and confiscate infringing products. Counsel for holders of copyrights, trademarks and patents should enlist CBP to keep infringing products out of the country. Counsel should record company trademarks and copyrights with CBP at https://apps.cbp.gov/e-recordations/. To do so, the company first must hold a copyright registered with the U.S. Copyright Office or a trademark registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. The registration fee to record registered rights with CBP is $190. CBP also can exclude products that infringe patents, but patents cannot be recorded with CBP. Instead, counsel should seek an exclusion order from the U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC). Exclusion orders are called §337 orders, after §337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, now 19 U.S.C. §1337. CBP will enforce exclusion orders. The USITC initiates a §337 investigation when a complaint is filed. The complaint must identify the parties who allegedly violated §337. After a full evidentiary hearing, an administrative law judge issues an initial determination, and eventually the USITC may issue an exclusion order barring the products at issue from entry into the United States, as well as a cease-and-desist order directing the violating parties to cease certain actions. CBP has more than 300 ports of entry and thousands of officers trying to enforce a multitude of laws at the borders. A vigilant attorney should visit the relevant ports that infringers are likely to use and instruct examining officers what to look for. But finding the relevant port is not always simple. Counsel for an importer can use one of the many online subscription services, such as PIERS and Import Genius, to reveal which ports competitors and suspected counterfeiters are using. The CBP website is useful. There, lawyers can find contact information for CBP's intellectual property rights help desk, plus port addresses and contact information. In an Interim Rule published in the April 20 Federal Register, CBP?? made the startling admission that, "[d]ue to the development of sophisticated techniques of some counterfeiters and the highly technical nature of some imported goods, it has become increasingly difficult for CBP to determine whether some goods suspected of bearing counterfeit marks in fact bear counterfeit marks." This is CBP's plea for intellectual property rights holders' help to determine whether particular imported shipments are piratical. CBP is barred from revealing an importer's shipment information (deemed a trade secret) to other parties, including the holders of intellectual property rights. But CBP now will be able to share serial numbers, universal product codes and SKU numbers with intellectual property rights holders. By helping CBP inspect imported boxes and goods to determine whether a trademark is being violated, in-house counsel becomes an active partner in making sure fewer infringing products enter the country. If CBP refuses to enforce a company's rights, even when counsel has properly recorded them and obtained an exclusion order from the USITC, counsel may need to consider filing suit against CBP to enforce the exclusion order from the USITC. The Other Side CBP's recordation procedure is designed to avoid the typical protracted legal battles over who controls intellectual property rights. While speedy exclusion and seizure are ideal if CBP is stopping truly infringing products, the expedited system is less advantageous if CBP or the purported rights holder errs. The facts and law in this area are complex. Not only is it possible that CBP could exclude goods that do not infringe on recorded intellectual property rights, but it is possible CBP did not follow proper procedure when excluding or seizing clearly infringing goods. Counsel may need to take action. Counsel will know that there is a problem at the port when the importer receives a formal notice from CBP, perhaps a request for information or a notice of seizure or penalty. Sometimes, the notice is sent to an importer's customs broker. Importers may challenge a penalty or seizure notice or an exclusion order through administrative procedures and, ultimately, through the courts. It is becoming increasingly common to invoke CBP's procedural protections to keep out infringing products while simultaneously seeking a court's injunctive relief. Parties sometimes rush to sue or to get before an administrative agency as leverage, even when the merits are dubious. Companies may feel like walking away from a confrontation with CBP even when they are convinced they are not infringing upon anyone's intellectual property rights, thinking it all not worth their time and money. The problem is that the record is likely to haunt an importer in perpetuity. I know of no way to expunge CBP's records. If counsel's company has a record of infractions, CBP will detain and examine its shipments for weeks, disrupting the "just in time" business imperative under which most importers work. A company may not even know that it is importing infringing goods and will only discover a problem when CBP flags a shipment or when CBP audits the company. A company can request an advisory opinion, known as a ruling, from CBP to find out if a particular good is infringing. In-house counsel may want to set up procedures to audit the company's supply chain periodically. An experienced eye should be able to detect the clear red flags and subtleties that indicate possible infringement issues. ---------------------------------------------------- Oscar Gonzalez is a principal in Gonzalez Rolon Valdespino & Rodriguez in Dallas. His practice focuses on business/ corporate litigation and transaction law, international trade law and nonprofit organization law. Reprinted with permission from the June 11, 2012 edition of Texas Lawyer. © 2012 ALM Media Properties, LLC. All rights reserved. Further duplication without permission is prohibited.  Don't invite vampires into your home. It's a maxim that is surprisingly relevant to importers and exporters. Vampires may be just observing otherworldly etiquette or may be afraid of some sort of sanction (although it's hard to imagine what would scare the undead, other than being forced to watch Jersey Shore reruns). Unless you invite a vampire into your house, for whatever the reasons, the vampire cannot enter to do whatever vampires do. What do vampires do? Not to paint with too wide a brush, but vampires tend to run in monster mode most of the time. Scuttlebutt has it that there are movies and books targeted at wide-eyed teenage girls that portray vampires in a sympathetic light, but it's doubtful that parents anywhere would allow their daughters to date a vampire, especially not one who sparkles. And what do federal enforcement authorities do? Well, they enforce. They are always in enforcement mode. To invite them in to your place of business may open you up to all sorts of liability. It is generally not the smart thing to do. Now don't misunderstand. This is not to suggest that anyone should obstruct or impede federal authorities from doing their job. You should never do that. However, you may want to avoid doing their job for them. Beware enforcement officials bearing gifts. The government talks trade facilitation, but acts enforcement. If a cop were to drop by your home and asked you to come in. You'd ask why, and the cop would say, "we're doing community outreach and we just want to tell you what is legal or not legal. While we're here, you wouldn't mind if we looked through your computer, would you?" You laugh, but US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) uses a similar approach in Significant Importer Reviews, a cryptic program of suspect provenance and design. CBP claims that Significant Importer Reviews are informal, friendly outreach visits that allow importers of a certain size and volume and CBP to know each other without risk to either. The problem is that these outreach efforts can easily devolve into fishing expeditions. The other problem is that there are no formal guidelines or regulations regarding this program to restrain CBP from overreaching. Indeed, CBP has not reduced any of the program goals or guidelines to writing, a red flag to importers if there ever was one. Outreach efforts from enforcement authorities can harm exporters as well as importers, of course. Take, for example, Powerline Components Industries, a company that is currently featured by the U.S. Bureau of Industry and Security on its website (which is not a good thing). Powerline shipped diesel engines to Syria without the requisite license. The question for export enforcement authorities was whether the violation was intentional because if it was, then the penalty could be stiffer. Just about the time it was about to ship, enforcement officers paid a friendly outreach visit to the exporter during which the officers described the nightmares that befall violators of US sanctions laws. With that warning, Powerline knew or should have known that the export was illegal, i.e., it had the requisite intent. Enforcement authorities had little trouble forcing the company to pay a hefty penalty. A vampire could not have done better. |

Oscar Gonzalez

Principal and a founding member of GRVR Attorneys. Archives

September 2016

Categories

All

|

- Home

- Who we are

-

Our Practice

- Customs and Import

- 301refunds

- Export

- Litigation

- Section 232 and 301 Tariffs

- Outsource Your Classification

- CBP Audits

- Fines, Penalties, Forfeitures, and Seizures

- Customs Brokers

- C-TPAT >

- Foreign-Trade Zones

- Antidumping and Countervailing Duties

- Intellectual Property RIghts

- Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

- Manifest Confidentiality

- Contracts and Incoterms

- False Claims Act and Whistleblower

- Blog

- Resources

- Calendar and Events

- Best Customs Broker Exam Course

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed